Armed Resistance, De-colonial Cinema, and The Wind That Shakes The Barley

A look into the nature of violent armed resistance, imperialism, socialist filmmaking, and the role cinema can play in reframing colonial history.

"I'd kill a communist for fun, but for a green card, I'm gonna carve him up real nice." – Tony Montana, Scarface (1983)

I recently watched Ken Loach's Palme d'Or-winning war epic The Wind That Shakes The Barley; a captivating drama that unflinchingly examines the brutality of the British Empire's occupation of Ireland and the revolutionary movement that arose as a result – one that was ugly, as it needed to be.

The film is terrific. What sets it apart from other similar movies, including empathetic, revolutionary stories, is that it's less about the horrors of war and more about the necessity for violent resistance. That the responsibility of the people killed by revolutionaries is on the occupier – for it is because of the occupation that the resistance exists.

So often, the framing of revolutionary struggle – in both the media and cinema – makes it seem like there are two (or more) warring factions in an ideological conflict, and that both need to chill and give peace a chance. But things are rarely ever like that.

Even the few movies that are sympathetic to revolutionary causes generally put the occupier and the occupied on level playing fields. As if those resisting the Empire are as complicit in the death of innocent people as the Empire itself. As if they should simply take it easy and resist peacefully.

The problem, though, is that your occupier does not give you your freedom if you ask nicely. If they were that benevolent, they wouldn't be occupying your land and terrorising your people in the first place.

Still, people often feel uneasy about the notion of violent resistance and invoke Mahatma Gandhi's example. After all, Gandhi managed to resist the Empire peacefully. Why not follow in his footsteps?

The Gandhi Problem

Unfortunately, many who say so are oblivious to the fact that the British Empire was crumbling and that pulling out of the subcontinent after the end of World War Two became necessary, notwithstanding Gandhi's nonviolent resistance.

Figures like Gandhi are put on a pedestal by the colonisers themselves because exploitation without retaliation is what they want. For this very reason, the ruthlessness of some of Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr.'s revolutionary tendencies have also been revised to more palatable, ahistorical "peaceful resistance, no matter what" rhetoric in contemporary discourse.

Movies like Gandhi (1982) and Mandela and de Klerk (1997) play a significant role in constructing these simple narratives. Gandhi barely dips its toes into the nature and extent of the Empire's racist crimes, instead putting much of the focus on infighting during the partition of India and Pakistan – hastily carried out by a rich white man with no care, regard, or respect for the people of the region – barely even acknowledging the de-colonial process the Empire was forced to carry out after the end of the Second World War.

In the almost 200 minutes that Gandhi runs for, there is an obfuscation of the crimes of the Empire and no mention of the revolutionaries who were massacred by Britain for resisting occupation. Instead, we get an ahistorical "be peaceful and civil, and everything will be fine" story. Gandhi won eight Oscars.

Since, more often than not, critically lauded and award-winning films about oppression, revolution, and colonialism are similar to Gandhi, I was a little apprehensive about watching The Wind That Shakes The Barley – even if it was directed by Ken Loach, one of contemporary cinema's few genuinely progressive, left-wing filmmakers. And for the same reason, I was genuinely surprised, relieved, and impressed when the credits started to roll.

Revolutionary Framing in The Wind That Shakes The Barley

The Wind That Shakes The Barley is less Gandhi and more The Battle of Algiers, the exceptional 1966 film about Ali La Pointe's revolutionary struggle against Algeria's brutal and racist French colonial occupiers.

In The Battle of Algiers, director Gillo Pontecorvo poignantly captures how the barbarism and horrors caused by those resisting occupation are, ultimately, always on the occupier. In The Battle of Algiers, revolutionaries murder civilians, yet even as you sympathise with those killed, Pontecorvo makes you understand why the responsibility for those killed is borne by the French Empire, who occupy and brutalise Algerians on their own land.

Like The Battle of Algiers, The Wind That Shakes The Barley nails this crucial matter. The film focuses on the IRA's resistance against the occupying British Empire, as well as their internal conflicts – yet those killed by the IRA, including their own family members and childhood friends, as well as British soldiers, are because of the Empire's merciless occupation, racism and exploitation.

Ken Loach, who has always been a committed Socialist auteur and was expelled by Kier Starmer's Labour Party in August 2021 – a badge of honour for any serious leftist – clearly gets this. Yet so many, including well-intentioned, compassionate filmmakers, unfortunately, do not.

Hollywood and Israel’s Genocidal Rampage in Gaza

Perhaps there's no better example of the reluctance of so many storytellers to engage with the nature of resistance than the fact that even today, after 10 months of genocide, which has seen the Israeli government withhold aid while flattening Gaza and its civilians with indiscriminate bombs, there have been so few Western filmmakers who have called for a ceasefire, because "Hamas is evil and needs to go", refusing to engage with the uncomfortable reality that Hamas – like the IRA, the FLN, or any other resistance outfit – exists because of a violent, belligerent occupation.

In the rare instances where prominent filmmakers have sympathised with the Palestinians, like Jonathan Glazer at the Oscars, they have been hounded and smeared by the media and the Apartheid State. The same Apartheid State that has been paying Elon Musk to disseminate genocidal propaganda to justify killing children in Gaza.

The framing, across the political class and corporate media, has, for the last 10 months, consistently remained that Israel's genocidal rampage in Gaza was instigated by the Hamas-led attacks on October 7, even among many who are sympathetic to Palestinian victims and feel that Israel has gone too far. "There was a ceasefire on October 6," shriek privileged liberal voices from suburbia deep inside the imperial core. No, there was no ceasefire on October 6. There was a belligerent occupation, of both Gaza and the West Bank. An occupation that has always treated Palestinians with nothing but apathy and disdain.

In fact, the parallels to the resistance in Algeria, Ireland, and any other occupation are unmistakable. Not only is it that Hamas' existence is borne out of the occupation of Palestine, but so is the framing of, and the manufacturing of convenient timelines for, the violence carried out by each of these resistance outfits. The IRA's killing of British soldiers and civilians, bus bombings and kneecappings have also historically been portrayed as the heinous, savage and indefensible acts of a beastly people, never engaging with the crimes the Empire committed against Irish civilians that instigated them.

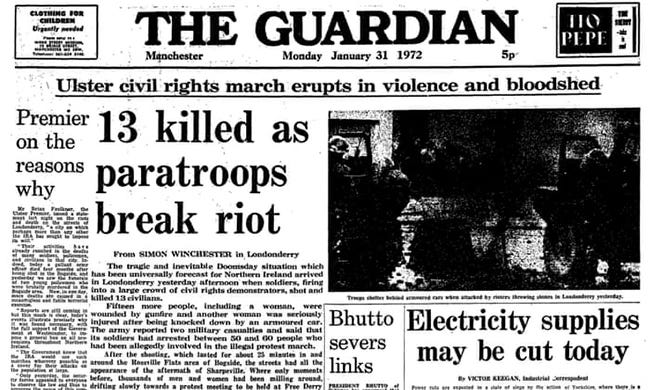

One of the most prominent examples of the blatant disregard for Irish civilians and the crimes committed by the Empire is in the British press' coverage of Bloody Sunday – a massacre carried out by British soldiers who shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest in Derry on January 30 1972, killing 13, which became 14 months later when an injured civilian succumbed to their injuries.

In the immediate aftermath of the murder of civilians protesting occupation, the British press framed it not dissimilarly to how they frame the murder of Palestinian civilians today. On January 31 1972, The Times headline was: "13 civilians are killed as soldiers storm the Bogside" and "March ends in shooting". The Guardian's was: "13 killed as Paratroopers break riot" (rather than "Paratroopers kill 13"). The Daily Telegraph went with "13 shot dead in Londonderry", "Banned march erupts into riot", and "IRA fired first, says Army". The Daily Express headline was "Gun Fury" and "Paras face 'fusillade' then open fire". There are plenty of other examples, and I won't bore you with them all.

From 1988 until 1994, the British government also banned radio and TV broadcasts of the voices of representatives from Sinn Féin and other republican and loyalist groups – the lunacy of which is touched upon in the TV series Derry Girls.

These attitudes continue to persist and are not limited to Palestine, either. They plague anywhere there is a government that does not serve Imperial interests. For example, the American (and British and European) press continues to cover Cuba and its revolutionary government with malicious misrepresentations, often euphoric with glee anytime there is a protest against the revolutionary government – no matter how insignificant – entirely omitting the fact that the country has been ravaged by a continuous and illegal US-led economic siege.

More recently, the US Government has refused to recognise Nicolás Maduro as Venezuela's president a mere fortnight after congratulating neoliberalism-friendly Paul Kagame for winning the Rwandan Election with 99 per cent of the vote for the third election in a row. US-based corporate media has refused to engage with this hypocrisy, as well as the impact of the US' cruel sanctions on Venezuela – which has more oil reserves than any other country in the world – parroting US State Department perspectives instead.

The same has always been true for the framing of any resistance to land theft, occupation and genocide – in the media, as well as in cinema. In fact, Hollywood played an insurmountable role in dehumanising Indigenous Americans in early 20th century American movies.

In the 20th century, Native Americans were regularly presented through racist stereotyping, portrayed as savages who resisted civilisation and took joy in killing white settlers. Some Hollywood films, including Universal Studios' 12-part 1939 movie series Scouts to the Rescue, simply used English in reverse as a substitute for Indigenous languages.

One of the most common tropes to show the savagery of Native American tribes in both Hollywood and the media was by centring on the act of scalping – physically cutting off white settlers' scalps, with their hair attached – after killing them.

How savage must a people be to do something like that?

Well, the fascinating thing about scalping is that the act was carried out by some Indigenous American warriors resisting land theft as retaliation because it was what European settlers had been doing to Indigenous civilians after killing them, something completely omitted from Hollywood and the media in favour of palpable revisionism to dehumanise all Native Americans and make the crimes committed against Indigenous Americans easier to digest.

The parallels to Israel's ongoing genocidal rampage and its framing in the media and parts of the entertainment industry are eerily similar. We have no evidence that Hamas fighters beheaded babies, yet we have seen videos of Israeli bombs beheading not only babies but journalists, too. We now also have leaked footage of Israeli soldiers raping a Palestinian detainee at the Sde Teiman torture camp, yet, like the act of scalping has always been tied to Native American warriors and not America's European settlers, the brutality of the violence is tied solely to Hamas, and not the Israeli Occupying Forces.

How the Wind That Shakes The Barley Pushes Back Against Colonial Narratives

The Wind That Shakes The Barley, unlike many other war films, does not distort timelines and puts the brutality of occupation front and centre. Our protagonist, Damion (Cillian Murphy), is a doctor who is entirely detached from the resistance and wants to go to work in London. It is only when the inhumanity of the occupation comes directly to his community that he takes up arms. This framing is crucial. Like how Hamas was borne out of apathy for the Israeli occupation and how Indigenous resistance in the land we now call the United States arose from manifest destiny, the IRA was borne out of apathy for the Crown's occupation.

Loach, who has been an ardent supporter of the Palestinian right to self-determination and statehood and has been a supporter of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement for years – to the rage of the Israeli government – makes this a crucial facet of his film. He goes to great lengths to contextualise the conditions of occupation and resistance, which, through a story told with well-constructed characters, makes The Wind That Shakes The Barley an excellent work of art to understand the essence of resistance and revolutionary violence. It is also an example of how uniquely effective cinema is as an art form and why we need more de-colonial, revolutionary movies.

If Katheryn Bigelow had directed The Wind That Shakes The Barley, the film would start with Damion killing young British soldiers, and the rest of the film would centre on the Empire's manhunt of Damion with no regard for the lives of those "complicit", who would be tortured to the glee of nationalist audiences. If Alex Garland directed The Wind That Shakes The Barley, the IRA, the Free State, and the British Empire would all kill a bunch of people, and the message would be "war is bad".

Why We Need More Revolutionary Cinema

When films like Zero Dark Thirty and Civil War plague Hollywood and are universally recognised as good films, the attitudes towards Empire, nationalism, Israel, and occupation should, really, come as no surprise. Films like those are rampant, and The Wind That Shakes the Barley or The Battle of Algiers are the rare exceptions.

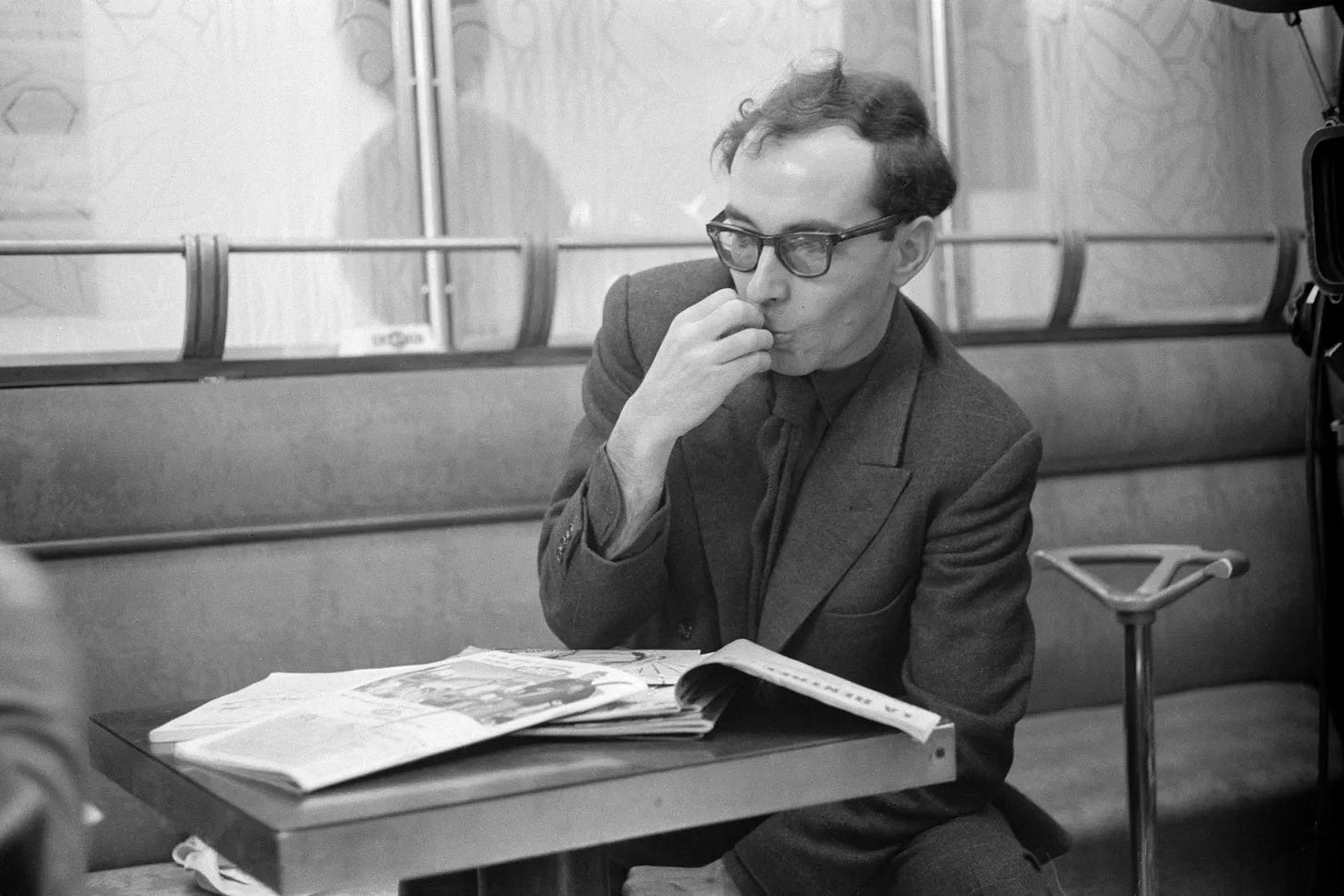

In fact, despite being an ardent fan of movies – especially revolutionary cinema – I can only think of two auteurs who have been able to regularly bring anti-imperialist perspectives to mainstream audiences worldwide. Loach and French maestro Jean-Luc Godard.

Even still, Loach is unheard of among many moviegoers. Everyone knows who Christopher Nolan, Greta Gerwig, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino are, but how many have seen, or even heard of, Ken Loach's movies, even if he is one of only nine filmmakers who have won the Palme d'Or twice?

Godard is also mostly known for his earlier works – which, albeit brilliant and politically charged – find the crux of their contemporary interest focused on the French New Wave, the prowess of his technical filmmaking, and Anna Karina's presence in his movies. Godard's most politically charged works, such as Ici et Ailleurs, which parallels the Palestinian revolutionary struggle with the life of a privileged French family, and Tout va bien, a film about class struggle underpinned by a scathing criticism of capitalism, remain unknown to many.

Unfortunately, the Marxist and anti-imperialist political legacy which underpinned Godard's movies is obfuscated by many critics and cinephiles, even as they recognise him as one of the best auteurs of all time.

Godard and Loach are just the two best-regarded left-wing filmmakers. There are so many other revolutionary filmmakers from around the world who, despite reaching local and indie audiences, are practically unheard of globally, even by me, who lives for revolutionary cinema.

It is particularly disheartening because cinema is perhaps the singular most potent means of helping people understand the other. It helps people understand the lives and realities of communities completely detached from them and, even more crucially, helps people make sense of their own existence and the world they live in. Recent releases like I Saw The TV Glow, Sound of Metal, Aftersun, and even Barbie are examples of just that, but as far as contemporary cinema goes, options are few and far between.

I would argue that movies have the capacity to help people understand de-colonial resistance, power dynamics, and the nature of violence under occupation better than perhaps any other medium of art, including books.

The Battle of Algiers serves as an excellent example of just that. Despite having been made over half a century ago, Pontecorvo's movie captures the essence of guerrilla warfare better than many books do – also making it very accessible to those who do not come from formerly colonised (or currently occupied) countries. The Battle of Algiers has been studied by the US Department of Defence as well as revolutionary groups, such is its potency in helping understand all things occupation and resistance.

Helping people understand the immorality of occupation and the need for revolution is one thing, but diving into the extent of the brutality that underpins occupation and colonialism is a whole other beast. There are still so many people who play off colonial exploitation by saying things like: "But they did some good things, too." A commonly made argument in favour of British colonialism of the subcontinent is that the Empire developed a comprehensive railway network, much of which continues to form the basis of Pakistan and India's railway industries.

What is conveniently ignored – whether maliciously or simply from a lack of knowledge because of the framing in British textbooks and films like Gandhi – is that this comprehensive railway network was created to be able to transport the plundered wealth of the resource-rich subcontinent away to her majesty's island.

Economist Utsa Patnaik carried out extensive research into the wealth stolen from the subcontinent by the Empire and found that Britain drained an estimated $45 trillion worth of goods from the subcontinent from 1765 to 1938. To put this figure into perspective, it is 15 times greater than the UK's 2022 GDP. The US and China – the world's richest countries – have a combined GDP less than the wealth stolen by the British Empire from just the subcontinent during their period of belligerent colonialism – which also saw them cause a famine in Bengal that killed an estimated three million people.

While much of the defence of colonialism stems from and is rooted in racist, nationalistic, prejudicial and orientalist attitudes, it is also important to reiterate that many simply have not been taught of the crimes of Empire or the nature of occupation and the necessity for resistance. The same rings true for Israel's century-long occupation of, and ethnic cleansing of, Palestine.

This is not just a consequence of ignorance, either. It is carefully manufactured by the Western Imperial powers – which stand as the only countries in the world to continue to refuse to recognise the right of the Palestinian people to a state, with many of these very states built over the graves of their Indigenous populations, too. This is why revolutionary cinema is so important to push back against the presiding narratives and help people understand the simple realities of oppression that they have been told are complicated or religious.

Many have grown up being told that the IRA were savage terrorists because they carried out bus bombings and killed innocent civilians instead of protesting peacefully – as if your racist, brutal occupiers would give you your rights because you asked nicely – but if we get more films like The Wind That Shakes The Barley that engage with colonial and revolutionary history, the conditions that underpinned the IRA's revolutionary violence – and those of many other occupied peoples – become easier to understand.

This does not mean you need to celebrate the killings of innocent civilians. It merely means you need to understand that these killings and the safety of civilians in the occupying colonial powers are compromised by the colonial powers themselves by maintaining illegal occupations which treat indigenous populations with apathy.

The IRA's threat subsided drastically after The Troubles ended, even as the North of Ireland remains a part of the UK. The ANC stopped carrying out attacks when Apartheid was dismantled in South Africa. The FLN stopped carrying out attacks after the Évian Accords were signed and Algeria became independent.

Armed resistance is a product of colonialism and occupation, and it ceases to need to exist in the absence of belligerent foreign occupation. Terrorist designations, inaccurate coverage wholly ignoring the crimes of the occupier, and convenient timelines to obfuscate the situation do not change existing realities.

The Farha Effect

Much like films about the necessity and inevitability of armed resistance like The Battle of Algiers, de-colonial cinema that lays bare the brutal crimes of the occupier is also crucial in defining the conditions that bring about revolutionary struggle.

There is probably no better contemporary example than that of Farha, Darin Sallam's 2020 film about the Nakba – the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from their ancestral homeland – told through the eyes of a 14-year-old Palestinian girl.

The Israeli government tried to block Farha from streaming on Netflix, which backfired, as it allowed this independent film, which premiered to a positive but lowkey audience at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2020, to gain mainstream attention. Farha now stands as one of the most recognisable movies about the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and has played a monumental role in helping many understand the brutal occupation that underpinned the creation of the Israeli state.

A few months ago, I interviewed Rachel Aoun, the Lebanese cinematographer of Farha, and she spoke to me about the unique impact that cinema can have in helping people understand the plight of communities they share little in common with.

Speaking about her work on Farha, Aoun said: "It was very important for us to put context into the struggle of the Palestinians."

She also mentioned how the film coming to Netflix in December 2022, just a few months after Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was murdered by the Israeli Occupying Forces on May 11 2022, was important, as it finally offered people a chance to see a movie about the Nakba, based on the accounts of survivors, at a time when there was global attention on Israeli war crimes the plight of those in Gaza and the West Bank.

"I felt like it's about time that Palestinian stories got attention," she told me. "It was also eye-opening for me, even though I'm Lebanese and knew the history of the Palestinian struggle.

"Farha was important then [when it premiered on Netflix], and it's even more important now [months into Israel's genocidal rampage in Gaza] because people can understand the Palestinian struggle and share it on social media to help more people understand it."

Farha has now become the most popular and recognisable Palestinian film ever made – in part because of the Israeli government's unsuccessful attempts to get the film taken off Netflix – and has become instrumental in helping people learn about the ethnic cleansing of Palestine through a brilliantly shot 100-minute feature from the lens of a 14-year-old Palestinian girl who's life is ruined by brutal settler colonial violence.

Watching Farha is more harrowing, grim and infuriating now than ever before, as you cannot help but think of the thousands of girls and boys, aged 14 or less, who have been killed, amputated, or will forever be plagued with irrecoverable trauma because of what they have endured over the last ten months as Israel continues to flatten Gaza, burying militants, Palestinians and Israeli hostages alike under the rubble of destroyed buildings.

Farha was an independent film that was only able to have the impact it had because of the Israeli government's unsuccessful attempts to have it taken off Netflix, yet it has still had a monumental impact in helping many around the world understand the Palestinian struggle. It shows just how powerful de-colonial movies can be.

What Can We Do?

For the left-wing cinephiles reading this piece, the onus is on us to amplify independent filmmakers from around the world, to help others de-colonise their minds. It is challenging, but so many of us – including myself – grew up with the same attitudes. If we've been able to claw our way out, we can help other, well-intentioned people do so, too. Engaging with de-colonial films and independent filmmakers from around the world, and explaining the nature of violence, imperialism, and colonial history to others is a small part of doing that.

For others who have still not clicked off (I appreciate you!), I urge you to engage with the challenging legacy of Empire and colonialism. I urge you to talk to those who grew up with the consequences of colonialism to inform your understanding of imperialism. I urge you to engage with the works of those who have unselfishly dedicated their lives to studying Empire and revolution. I urge you to be critical of the media – including progressive outlets – you engage with. And since I am a film guy, I urge you to engage with independent de-colonial filmmakers and movies – including the ones mentioned in this piece – which I hope can play at least some role in helping you see revolutionary struggles in a more critical light, which puts the focus on the accounts and perspectives of the victims and not the perpetrators.

Other films that I have not mentioned in this piece but are worth checking out include the recently released Kneecap, Elia Suleiman's The Time That Remains, Mikhail Kalatozov's I Am Cuba and Abderrahmane Sissako's Bamako. Some cool recently published books to check out include R.F. Kuang's Babel and Susan Abulhawa's Against the Loveless World. If you're a fan of podcasts, you should also check out Brendan James and Noah Kulwin's Blowback – which is meticulously researched, wonderfully presented, and staggeringly illuminating.

If there is one thing I want you to take away from this piece, it is that in spite of the general lack of de-colonial, Indigenous, and minority perspectives in mainstream movies – unsurprisingly as Hollywood is, after all, a hyper-capitalist industry built on top of broken promises, treaties and the graves of the Tongva, Tataviam, and Chumash tribes indigenous to the land we now call the United States – there are still some great films, made by independent filmmakers around the world. It is important to watch these films, amplify the voices of those most affected by colonialism and imperialism, and come to terms with the essence and necessity of revolution. Now, more than ever before.

We may not be able to do anything other than helplessly watch as a genocide is being carried out or as far-right white-nationalist thugs try to carry out pogroms in the UK, but we can always do more to inform ourselves and be hopelessly hopeful and strive for a future where we can try to push for reparations and right the wrongs of the centuries of oppression, colonialism, imperialism and exploitation that have shaped our unequal, oppressive world – even if it looks increasingly bleak every passing day.

"Who told you America is imperialist?" – Elia Suleiman, The Time That Remains (2009)